Executive Talent Magazine

the future of work in an age when automation and robotics are changing the global economy

The debate over whether technology represents an opportunity or a threat has gone on since Queen Elizabeth, trying to protect her subjects from unemployment, denied a patent application for a knitting machine in 1589. Scientists, academics and business leaders continue to offer different views on how technology will impact employment, the economy, and society.

In essence, reduced production costs result in better market prices. The increasing demand then triggers more jobs.

The most recent McKinsey Global Institute report explores the future of work in an age where robotics, data analytics, machine learning and artificial intelligence are changing the workplace and the global economy. Specifically, the study focuses on identifying jobs most likely to have some or all of their functions automated, factors that influence the pace of automation in the workplace, and the potential impact that automation could have on global employment and productivity. Along with McKinsey, thought leaders across industries and the globe are talking about automation and what it means in the world and the workplace.

Where we stand

Startling technological advances include computers that can lip read, and robots with a receptive surface that can “feel” through touch. Software programs and machines are mimicking, and in some cases outperforming, humans.

For example, a program called “Wordsmith” can take box scores from a sporting event or financial data and produce written narratives that are nearly impossible to distinguish from stories written by journalists. One start up, Enlitic, is applying machine learning to medicine. In tests, the technology outperformed a panel of radiologists in classifying tumors and detecting fractures. The Wall Street Journal reported in December 2016 that Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund with about $160 Billion under management, is working on “technology that would automate most of the firm’s management.”

The Google Translate team has developed an app that transforms smartphones into a talking translation machine, with the ability to handle about two dozen languages so far. “The app works very well, as long as sentences are kept relatively simple. For instance, someone who wants to tell a taxi driver in Beijing that he urgently needs to get to a pharmacy simply has to speak into his smartphone in, for example, German, and it promptly repeats the sentence in Chinese, correctly but in a somewhat tinny voice: "Qing dai wo qu yijia yaodian."

Influential German computer scientist Franz Josef Och feels that the application is still "slightly slow and awkward, because you have to press buttons." The quality of the translation is also inconsistent. But only a few years ago, people would have said he was crazy if he had predicted what Translate could do today.

From Der Spiegel, “Google's Quest to End the Language Barrier,” September 13, 2013.

Stafford Bagot, Regional Managing Director at Heidrick & Struggles, Singapore, puts the advantages of technological advances into context. “If you look at the civil construction sector, the focus in recent years has been more and more all about precision, speed and quality of the projects. The jobs that are now done by robotics and automation have impacted the human capital element in the sector, this has a knock on affect, including jobs and employees that service those machines.”

Will technology supplement or supplant the human workforce?

Martin Ford’s 2015 Rise of the Robots chronicles how robotics and machine intelligence could replace the human workforce, and the destructive implications for the economy. It is a dark view, in contrast to the more moderate belief expressed by economist and researcher James Bessen. Bessen observes that as electronic discovery became a billion dollar business, jobs for legal support personnel outpaced the labor market. ATMs had a similar impact on the number of bank teller jobs. “On average, since 1980, occupations with aboveaverage computer use have grown substantially faster.”

The McKinsey research introduces some nuance to the shifting workplace. “As processes are transformed by the automation of individual activities, people will perform activities that are complementary to the work that machines do (and vice versa). These shifts will change the organization of companies, the structure and bases of competition of industries, and business models.”

Suzanne Burns is a member of Spencer Stuart’s global Industrial and Digital Practices based in Chicago. Burns describes a client who makes material handling conveyor systems used to move products down a factory or distribution center fulfillment line. “Along the conveyer were sensors that indicate whether a box was stuck on the line and the speed at which the products were moving. We recruited someone from Silicon Valley who understood software applications, and embedded new logic to gather and aggregate data from the sensors. This database now delivers information on facility productivity, bottlenecks, and how to run the line more efficiently. This allows the customer of the material handling system to fine-tune their operations.” She explains, “With that increase in efficiency, a manufacturer or distributor can get more boxes out the door, improve their growth rate and their profitability, and make decisions about facility optimization investments with information that they never had before.”

In the conveyor belt example, technology improves efficiency and productivity. Rod Keller, Partner in the Odgers Berndtson Technology Practice, Austin, explains, “Automation is really the continued pursuit of operational efficiency and better customer insight, and the company that leads in operational efficiency almost always has the advantage.”

Keller adds, “Automation will replace human labor on routine tasks, but I don’t see humans losing their jobs. People in the workforce need to understand why we’re doing it, the benefit to them, and what new role they’ll play. The biggest benefit is freeing employees up from doing routine work to doing more analytical work. The quality of what we do improves, and as quality improves. productivity goes up and customer satisfaction increases, leading to higher revenues and profits. The workforce understanding their value and the role they play is key, and most C-level folks just blow that off.”

The Roles at Risk?

“A farming plant like this requires about half the amount of human workers our existing facility for lettuce production without automation does. We grow in a highly controlled environment, and the plants themselves are mostly handled by machines and robots. This is in part done to increase efficiency. Apart from automation, we also use water saving technology and pesticide-free cultivation,”

J.J. Price, Global Marketing Manager at Spread, Forbes, May 16 2016.

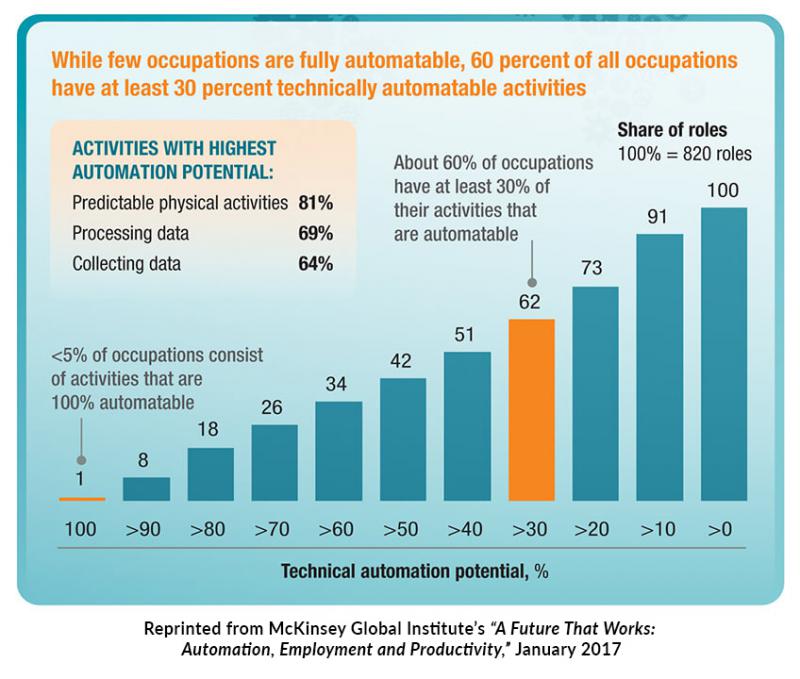

The McKinsey research team used the state of technology in respect to 18 performance capabilities to estimate the technical automation potential of more than 2,000 work activities from more than 800 occupations across the US economy, and then broadened their analysis across the global economy. Those performance capabilities were broken down into five groups: sensory perception, cognitive capabilities, natural language processing, social and emotional capabilities and physical capabilities.

The researchers were able to “assess the state of technology today and the potential to automate work activities in all sectors of the economy by adapting currently demonstrated technologies.”

On either end of the McKinsey findings:

- Almost one-fifth of the time spent in US workplaces involves performing activities with the highest automation potential,

- Managing and developing others has the lowest automation potential, and accounts for the least of time spent in U.S. workplaces.

McKinsey researchers broadened their analysis to 46 countries, and determined that automation has the potential to affect activities associated with 40 to 55 percent of global wages, depending on the country, with that potential “concentrated globally in China, India, Japan, the United States, and the largest European Union countries—France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom.”

To illustrate the impact of automation in different scenarios, researchers explored hypothetical case studies in which automation increased speed, safety, efficiency, productivity and customer satisfaction, and significantly changed the nature of work, “which will likely affect all workers at all skill levels. There will be less routine and repetitive work based on rules-based activities, because this can be automated across many occupations and industries. This in turn will mean many workers may need to acquire new skills. The workplace will become ever more a place where humans and technology interact productively.”

William Farrell, APAC Regional Practice Leader at Boyden Executive Search, Shanghai, explains how employers are addressing these changes. “We do see more forwardlooking companies investing in their facilities while making sure their employees can work alongside the computers. Clearly, leaders need to do a good job preparing their staff to be more technically inclined, to attain and develop skills that are going to be required to be successful in a more automated workforce. Leaders also need to seek more entry-level candidates who have a technology background and who can be more competitive at an earlier age in their career.”

Simone Mears, Director at pac executive, Profusion Group, Sydney, says, “Automation also creates new jobs. It’s threatening to individuals who are in roles that are being replaced by computers, but I’ve always held on to the theory that you won’t lose your job to a computer, but you will lose your job to somebody who can use a computer.”

“So who is right: the pessimists (many of them techie types), who say this time is different and machines really will take all the jobs, or the optimists (mostly economists and historians), who insist that in the end technology always creates more jobs than it destroys? The truth probably lies somewhere in between. AI will not cause mass unemployment, but it will speed up the existing trend of computer-related automation, disrupting labour markets just as technological change has done before, and requiring workers to learn new skills more quickly than in the past.”

From The Economist, June 25 2016

Andrew MacAfee is the Co-Director of MIT’s Initiative on the Digital Economy. At the MIT Sloan CIO Symposium 2016 he said, “We are now building buildings where the first draft did not come from a human team of architects and designers, the very first draft came out of a computer, and it satisfied all the energy requirements, all the wind shear requirements and all the structural requirements. What the humans did was essentially iterate and tweak on top of that design. Even in very complex and relatively creative endeavors, the technology is actually taking the lead. This is a very profound inversion, and it’s early days. We’re going to see a lot more of it.”

How soon? Researchers at McKinsey identified five factors that will affect both the pace and the extent of automation. These factors include technical feasibility, the cost of developing and deploying systems, labor market dynamics, economic benefits, and regulatory and social acceptance.

Any potential automation transformation will take time. The availability of the technology is an important factor, and new tools are streaming into the marketplace with even more in the R&D pipeline. But investing in new technology, especially for early adopters, can be expensive. For example, Keller explains “4K (resolution in digital television and cinematography) is the next generation of HD. The software technology exists, but the cost of hardware to broadcast it is so high, it’s not going to happen until they get the costs down, until all aspects in the supply chain are aligned.” Weighing the costs and benefits of automation is complex, and includes indirect benefits such as improved safety and indirect costs including labor displacement that are harder to measure but nonetheless also drive corporate decision making. Finally, concerns about privacy, security, and liability as well as the fear of worker displacement are potential barriers to increased automation.

Thorbjoern Bahnson is Director and Head of Consumer Practice at Mangaard Partners/ TGCL, in Copenhagen. In the context of social barriers, Bahnson observes, “Automation is an enabler, if we get a chance to think about it first and decide how we want it to influence our future. There have been projects in human history where we may have taken the first steps without really thinking about where we were going. For example, maybe the nuclear bomb was not that wise. Maybe we are wiser now, and we will take the necessary time to think about what we want, with these new possibilities.”

To plot out the possible timing of the adoption and implementation of automation technologies, McKinsey researchers constructed a model scenario that estimates:

- When automation technologies will reach each level of performance across 18 capabilities;

- The time required to integrate these capabilities into solutions tailored for specific activities;

- When economic feasibility makes automation attractive; and

- The time required for adoption and deployment.

According to the report, “all of this could happen within two decades for a wide range of activities and sectors, but it could also take much longer. Whatever the time frame, the consequences will be significant, not just for individual workers and sectors but also for the global economy as a whole.”

Global productivity

“Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.” Paul Krugman The Age of Diminishing Expectations

Robbie Allen is CEO & Founder of @ Automated Insights, the company that launched Wordsmith, a natural language generation platform that can write narratives based on data inputs. Allen said, “We can take box scores and turn that into a story on a sporting event, and we can take financial data and turn that into an earnings report.”

Allen said, “The Associated Press would publish 300 earnings reports per quarter, and now using Wordsmith they do 3000. I was surprised when we launched this, I thought we were going to get some feedback from journalists that they weren’t happy. I asked them and they’d say, ‘I hated writing earnings reports!’ The data comes in very quickly, and journalists are judged on how quickly they can get a story out. That’s optimal for software, not people.”

AP’s use of Wordsmith is an example of increased, rather than displaced, output— one factor of productivity. And even though the McKinsey report estimates that a very high proportion of job functions are vulnerable to automation, global demographic trends will actually necessitate significant increases in automation in order to sustain current levels of productivity. According to the report, “even with automation, a deficit of labor is more likely than a surplus.”

Many countries have an aging population leaving the workforce, coupled with declining birth rates. The result is the looming problem of too few workers in subsequent generations to maintain GDP per capita. McKinsey’s analysis projects productivity gains through automation that bridge that gap. “The working-age population in numerous countries is stagnant or falling and productivity growth is struggling to compensate. Whatever their economic structure, wage levels, growth aspirations, or demographic trends, countries around the world could benefit from adopting automation to maintain living standards and help meet long-term growth aspirations.”

Economies with a shrinking workforce may also depend on immigration to bolster productivity. Farrell says, “In countries where there is less immigration with a more static population you’re going to have a problem. In the US and parts of Asia where you have fairly mobile workforces, the impact of the declining population will be somewhat mitigated if there’s a greater flow of people across borders.”

Albert Hiribarrondo is Founder and CEO of ALSpective/TGCL in Paris, and specializes in Higher Education. “When I discuss automation with clients, the positions are mixed. There will be a strong impact on the education system at large, but not necessarily a decrease in the number of people needed by the system. More clients are looking at this as an opportunity to meet the needs of people in society and less as a risk for people employed in education.”

For some countries dependent on their low-cost labor to lift them out of poverty, the rise in automation could, at least in the short-term, hurt workers in emerging markets as producers of goods choose to automate rather than off-shore production. From Bloomberg’s Luke Kawa, globalization “pushed multinationals to move production to countries with cheaper labor costs than advanced economies, while [automation] effectively substitutes capital for labor in the production process.”

Another trend that could hurt emerging economies in the context of automation is that physical assembly accounts for a shrinking share of the value of finished goods. According to The Economist (Arrested Development, October 4, 2014) “much of the value of an iPhone, for example, derives from the original design and engineering of the product rather than from its components and assembly.”

Ready? Set, Disruption.

In a recent survey by the Pew Research Center, half the respondents said that by 2025, robots and other applications of AI will have replaced a significant portion of the workforce, including knowledge workers whose employment consists of more mental than manual work and requires decision making. The other half of respondents predicted a less dramatic change, but they too acknowledged that when machines can perform knowledge work, knowledge workers—lawyers, writers, managers, and executives are among their ranks—will be affected. From The Harvard Business Review Artificial Intelligence: Disrupting the Future of Work

There is a role for policy makers, employers, and workers themselves in preparing for disruption and leveraging the opportunity for productivity growth afforded by new technology. Prof. Erik Brynjolfsson, Director of MIT’s Initiative on the Digital Economy said, “In the economy we see increasing decoupling between productivity and what the median worker is doing. Median income has stagnated, employment stagnated, and the reason is organizations aren’t keeping up. Skills are harder to change than hardware and software. When organizations lag behind, that can lead to mismatch, a grinding of the gears. Organizations need to speed up adaptation with skills development and new business models.”

Corporations can also take a holistic approach to productivity. Liz Crawford, Head of Executive Search and Leadership Assessment at KPMG, Brisbane, says, “One of my clients is based in a developing economy and they are still very focused on using local people, but looking at how they can balance local labor with automation. They are also focused on developing leadership talent there in the emerging economy.” Crawford adds, “The client talks about developing local capabilities for the country, not just for their business. They can easily automate a lot of what they do, but they feel a responsibility to actually create some employment where they are.”

Employers and workers also share responsibility in preparing for change. Mears says, “The challenge for organizations is to understand where they are going to lose jobs, and the responsibility they have is to already be thinking about the development of new skill sets and retraining. It is not going to be okay for companies to think that their responsibility ends when they pay employees a redundancy to leave.”

As employers look to mitigate the skills gap, Burns warns that organizations cannot ignore the human factor. She says, “Humans can process change at a certain rate, and the technological opportunity to change may be coming at us at a faster rate than a human’s ability to absorb the change. Organizational leaders need to understand the appropriate rate of change, so that people stay more engaged, so they don’t burnout. Employees need to feel invested, and that they have some control over their own destiny and the change isn’t happening to them.”

Leaders from government, business, and education may need to leverage their distinctly human capabilities of creativity, compassion, and agility to transition displaced workers and prepare the next generation of employees. Hiribarrondo adds, “Every single company is thinking about the risk of being disrupted. What is fantastic about education is that technology in education can only be for good. If you impact one life, you impact humanity.”

The McKinsey report closed with this salient observation: “At its core, however, automation represents a considerable opportunity for the global economy at a time of weak productivity and a declining share of the working-age population. For corporate leaders, too, automation will reshape the business landscape and create considerable future value. How to capture the opportunities and prepare for the possible consequences will be a key political, economic, corporate, and social question going forward. This is not something that can be watched from the sidelines. Automation is already here, and the technological advances continue. It is never too early to prepare.”

Crawford reflects, “We’re not exactly sure what the extent of automation will be in the workspace, but we all anticipate that people will be out of traditional jobs and will work with more agility. They will need to neatly package and market their capabilities, as maybe five years from now people will not be “employed,” but rather will have their skills “rented” or acquired by organizations as and when needed.”

“Technology-fueled capitalist creative destruction is a messy and uneven process, and there will be twists and turns. The droids are taking our jobs, but focusing on that fact misses the point entirely. The point is that then we are freed up to do other things, and what we’re going to do, I am very confident, is reduce poverty, and drudgery, and misery around the world. I’m very confident we’re going to learn to live more lightly on the planet, and I am extremely confident that what we’re going to do with our new digital tools is going to be so profound, and so beneficial, that it’s going to make a mockery of everything that came before.”

Andrew McAfee, Co-Director, MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy The Harvard Business Review, 2016